SCIENTIFIC BACKGROUND

MMR machinery and function

Mismatch repair (MMR) is a cell repair mechanism of DNA damage sustained during cellular metabolism. The MMR complex consists of several proteins, the most clinically relevant of which are MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.1 These proteins function as heterodimers with canonical pairings between MLH1 (dominant) and PMS2 (recessive) and MSH2 (dominant) and MSH6 (recessive) (see Figure 1). Dominant heterodimers can bind with other MMR protein complexes, while recessive heterodimers degrade unless they bind with their dominant heterodimer pair. Under normal conditions, MMR complexes recognize and repair spontaneous DNA damage (single base pair mismatches, small insertions, or deletions) during DNA polymerase replication and recombination, ensuring genetic fidelity in future replication. When MMR proteins are altered through a germline or sporadic mutation, DNA replication fidelity is affected, and cellular DNA damage accumulates, leading to genome instability and tumourigenesis. If the pathophysiology of tumourigenesis occurs because of a germline mutation in the MMR complex, this is called Lynch Syndrome or Hereditary Cancer Syndrome.

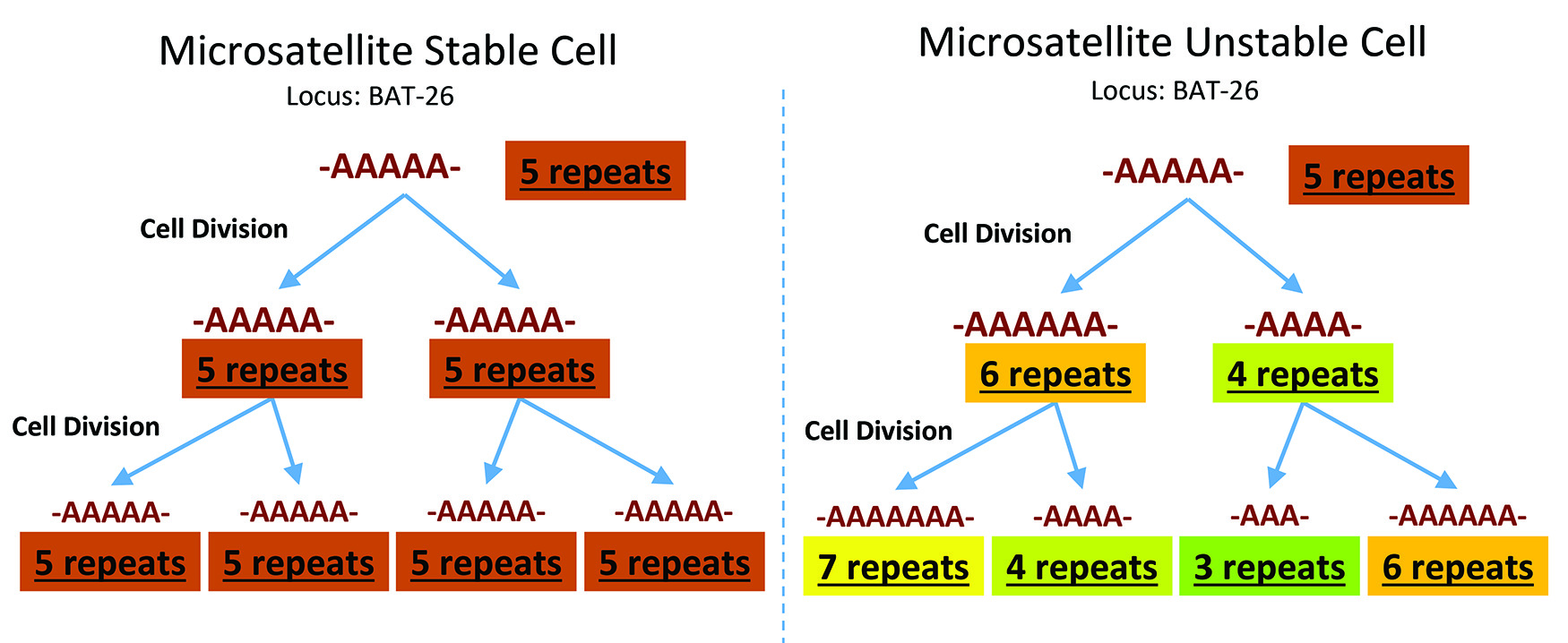

Microsatellite instability and its relationship to MMR deficiency

Microsatellites represent 3% of the human genome and are repeat short nucleotide patterns (typically GT or CA repeats) susceptible to reduced fidelity.2 Without an intact MMR function, each cycle of replication results in an accumulation of repeating errors, either insertion or deletion loops, occurring at these sites, resulting in an altered number of short nucleotide patterns between replication cycles. When the same number of short nucleotide repeats between each replication cycle, the cell is microsatellite stable (MSS). If there are differences between the number of short nucleotide repeat patterns at these conserved locations in the human genome, this cell has microsatellite instability (MSI) (Figure 1). The MSI phenotype reflects the MMR-deficient genotype. MSI demonstrates the activity of the MMR complex, while MMR IHC showcases the MMR protein expression; MSI testing and MMR IHC protein expression are complementary for MMR evaluation, but the terminology is not interchangeable. The gold standard for MSI is a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay panel consisting of five mononucleotide microsatellite repeats (i.e. BAT-25, BAT-26, MONO-27, NR-21, NR-24) and two pentanucleotide repeats used for specimen identification.3 With the advent and increased accessibility of next-generation sequencing, we can also identify MMR mutations via gene sequencing. The most common and available method for routine clinical practice is via immunohistochemistry (IHC) against the four major MMR proteins.

Lynch syndrome and the evolution of MMR testing

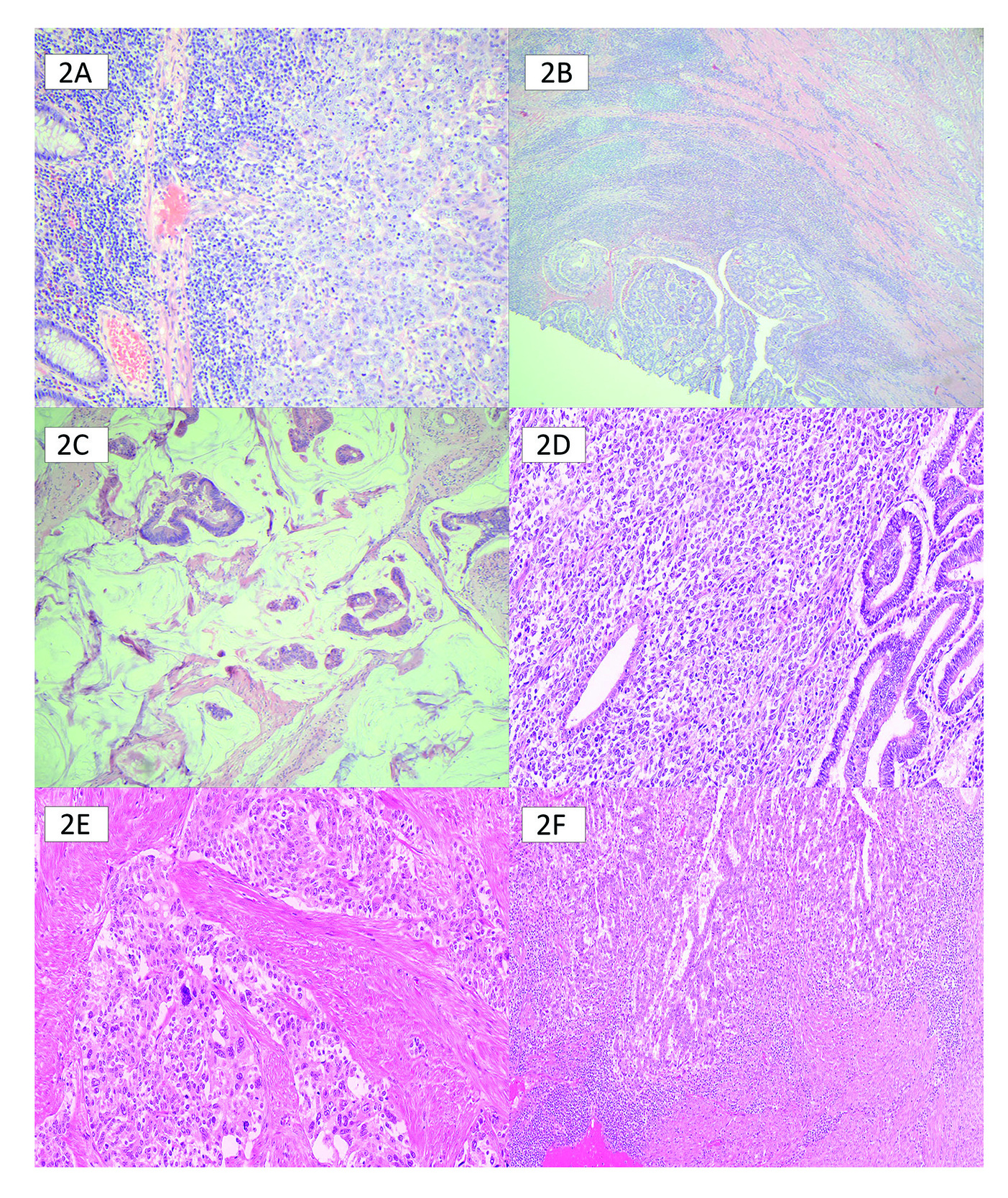

Approximately 0.3% of the population has Lynch syndrome, with Lynch-causing mutations found in roughly 3% of CRC and 2% of EC.4 The initial goal of MMR testing was to identify individuals with Lynch syndrome who possess an elevated lifetime risk of developing malignancies and to enroll them and their family members in high-risk, preventative screening programs. Stringent testing began for CRC patients using age-based and pathologic criteria such as Crohn’s-like inflammation, mucinous differentiation, and medullary patterns. This strategy had poor sensitivity and specificity (Figure 2).5 Similarly, in EC, starting with testing based on clinicopathologic characteristics such as tumours centred around the lower uterine segment, multiple tumours, tumour infiltrating lymphocytes, de-differentiation or undifferentiation, or ambiguous morphology, missed too many patients with Lynch syndrome (Figure 2). In 2016, the Canadian Agency for Drug and Health Technology (CADTH) recommended universal MMR testing in colorectal adenocarcinoma.5

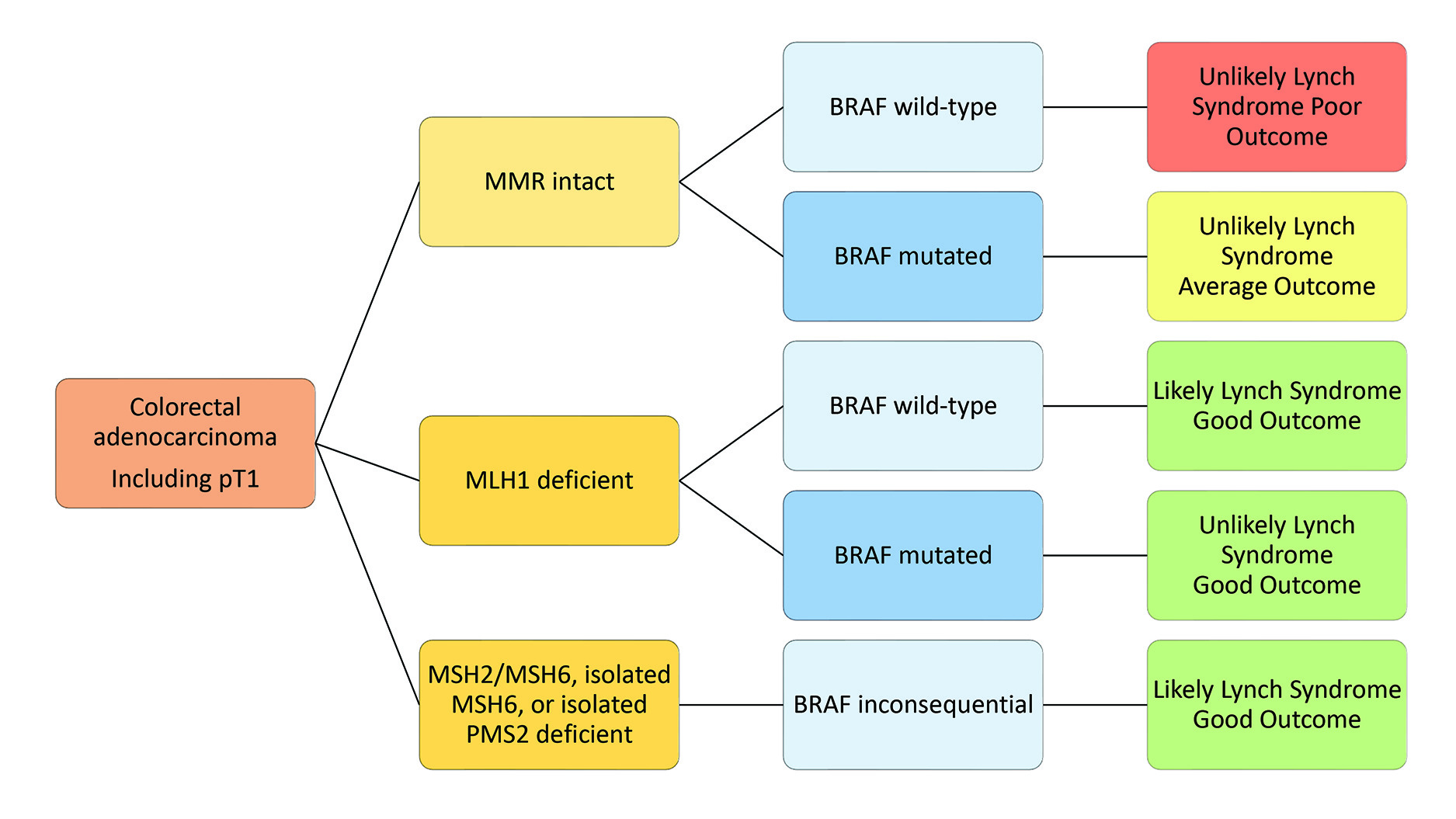

MMR testing in colorectal carcinoma

Approximately 230,000 new cases of cancer are diagnosed in Canada each year.6 CRC is the third most prevalent cancer in both sexes, accounting for 11% and 10% of new cancer cases in males and females, respectively. Accurate diagnosis, effective prognosis, and treatment options are paramount for CRC care. MMR and BRAF status offer prognostically significant risk stratification, as demonstrated in Figure 3. MMR-deficient tumours have a better prognosis than MMR-intact tumours.7 MMR also informs BRAF testing, a surrogate marker for sporadic MMR deficiency when MLH1 is deficient. Finally, MMR status is essential in informing treatment decisions in CRC. The mainstay of treatment for CRC is surgery, with the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy depending on stage. Most oncologists will not recommend adjuvant therapy for stage II tumours, while stage III and IV tumours will benefit regardless of MMR status.8 Classically, limited options existed for adjuvant treatment, leading to a linear escalation from FOLFOX/FOLFIRI and bevacizumab to alternating doublet chemotherapy and finally to anti-EGFR therapy, regorafenib, or clinical trials. The CRC treatment algorithm has become increasingly complex with recent advances in molecular biomarkers and advanced diagnostics. MMR deficiency specifically predicts benefit from immunotherapy in metastatic CRC, showing a two-fold increase in median survival from 8.2 months to 16.5 months when comparing chemotherapy to pembrolizumab.9 Currently, pembrolizumab availability in CRC depends on MMR status instead of PD-1 or PD-L1 as with other sites, further highlighting the importance of MMR status in therapeutic decision-making in CRC. CADTH has shown the most economical algorithm for MMR testing is universal MMR and BRAF testing.10

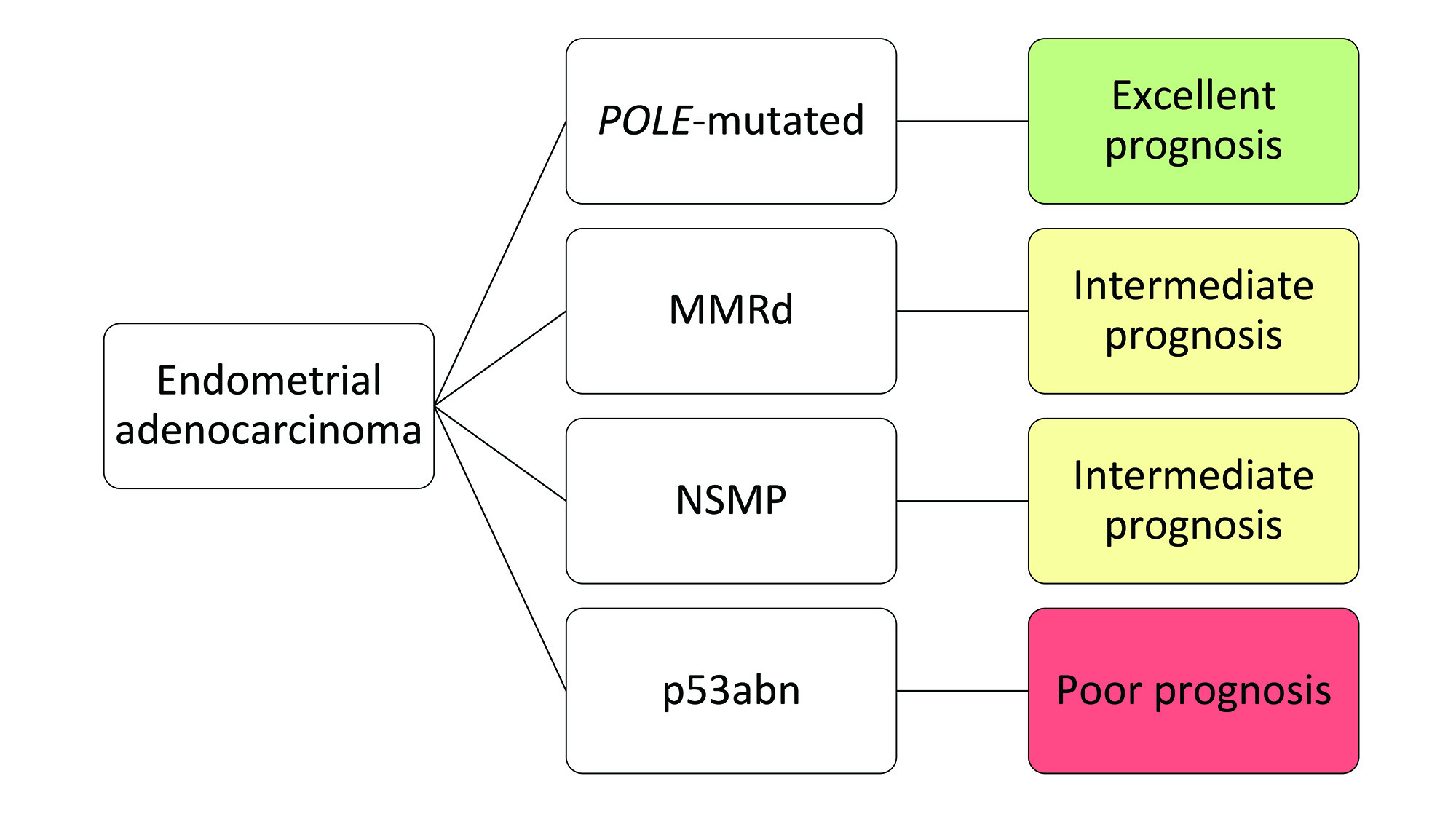

MMR testing in endometrial carcinoma

Endometrial cancer incidence is rising across the world.11 Several factors regarding EC treatment decisions hinge on using light microscopic criteria, such as histotype, lymphovascular invasion, and myometrial invasion, which have significant interobserver variation.12–15 Lack of reproducible pathological criteria leads to considerable variation in treatment, especially compared to molecular classification, including MMR.16 To improve standardization, the development of a molecular classification of endometrial cancer, ProMisE (Proactive Molecular Risk Classifier for Endometrial Cancer), utilizes MMR IHC, POLE exonuclease domain mutation sequencing, and p53 IHC (Figure 4).17 Integrating biomarkers to establish an EC molecular subtype has diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic effects. While POLE mutations are not the focus of this review, they can impact MMR interpretation. POLE stands for Polymerase Epsilon (ε) and is part of the DNA proof-reading system on the leading strand of DNA, providing a 3-5’ exonuclease function for mismatched base pairs. The fidelity of DNA replication with a functioning POLE is 10-6 to 10-7.18 This amount of proofreading is logarithmically more than the MMR complex. Therefore, when POLE is mutated, an EC patient has a much higher mutational burden (ultra-mutated phenotype) than an MMR deficient EC patient (hypermutated phenotype). The details and importance of how POLE mutations affect MMR IHC staining are discussed later. Still, because POLE mutation is associated with an abundance of other mutations, sometimes these affect MMR or TP53 genes, causing staining abnormalities or even loss. This is also true for MMR, a hypermutation phenotype, which can cause secondary mutations in TP53, affecting p53 IHC.

Like CRC, MMR status in EC carries prognostic, therapeutic, and diagnostic implications. The use of MMR IHC as a diagnostic tool has been helpful in EC because endometrial serous carcinomas are not considered to be represented in MMR-deficient EC, so the presence of MMR loss in an endometrial sampling with ambiguous morphology can be confidently interpreted as endometrioid subtype with an MMR deficiency. Additionally, it is helpful to use when trying to delineate endometrial adenocarcinoma from endocervical adenocarcinoma if MMR deficiency is present. Prognostically, patients with MMR deficient EC are more likely to have lymphovascular invasion and undergo lymph node dissection compared to MMR-preserved tumours. MMR-deficient tumours also convey a higher radiation sensitivity with lower chemosensitivity and are the indication that unlocks immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for EC patients.19,20 In summary, universal utilization of MMR IHC testing in EC along with p53 IHC and POLE testing allows for a better characterization of tumours than relying on histological data alone. Using molecular stratification in EC leads to more accurate risk stratification and access to personalized adjuvant therapy for patients.

MMR protein expression interpretation and testing algorithms

MMR IHC interpretation has evolved since its introduction into clinical laboratory use. Initially, a stringent, binary interpretation system required “all or none” immunoreactivity to signify intact expression or complete loss of tumour nuclear expression. At its core, MMR IHC provides a dichotomous and algorithmic readout of protein expression or loss of expression. In the most simplified state, complete loss of MMR protein expression represents a mutation in said MMR gene. And with a four-antibody panel, there are five standard interpretation readout patterns (Table 1). All proteins showing intact expression confirm an MMR-proficient result. Any of the other combinations of loss bestow a deficiency pattern of interpretation. Because of the heterodimer relationship, when a dominant heterodimer (i.e. MLH1 or MSH2) is mutated, it will not only show a loss of protein expression of the dominant heterodimer but also the recessive heterodimer as linkage occurs with the dominant heterodimer. Isolated loss of the recessive heterodimers typically means gene mutation of the recessive gene showing loss of protein expression.

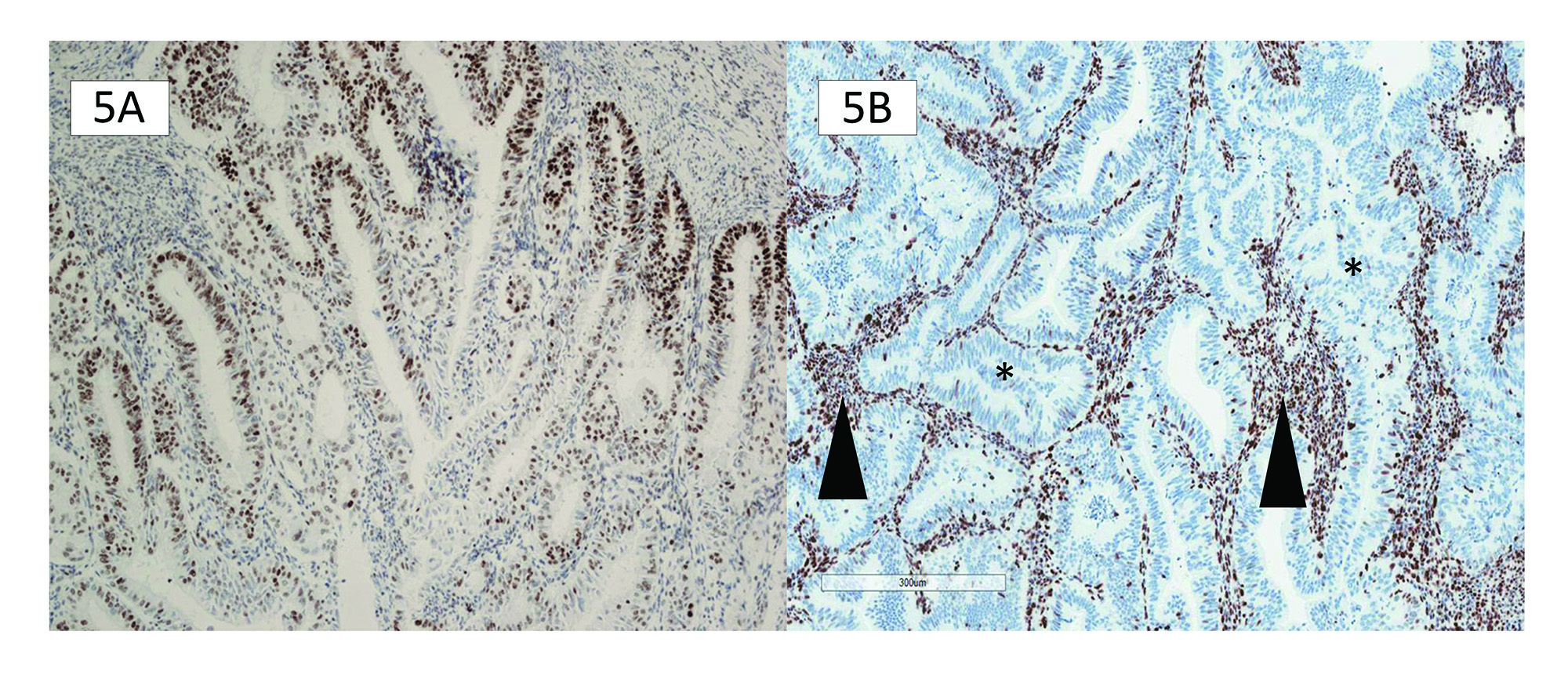

As clinical use of MMR IHC increased in prevalence, it became evident that sometimes “all or none” pattern did not capture issues encountered in everyday practice, largely fixation artefact in excisional specimens. Attempts were made to assign an arbitrary percentage cut-off to how much staining would need to be present: 1%, 5%, and 10% cut-offs were suggested (Figure 5A). These attempts to expand intact patterns did not address other biological entities, such as subclonal loss and weaker-than-internal control staining patterns identifying effects from hierarchical molecular impacts (Table 2). There is a need to move past the 1%, 5%, and 10% cut-off and instead use an interpretation of MMR protein analysis based on the pathophysiology. We now recognize four different interpretation staining patterns: intact protein expression, complete loss of protein expression, subclonal loss, and weaker than internal control staining.

Internal controls

There are several internal controls to help assess whether the MMR antibodies have been applied to properly fixed tissue. It is recommended that stromal cells, benign epithelial crypts, and tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes be evaluated when interpreting MMR IHC for protein expression or loss (Figure 5B). The intensity of the internal control staining is essential to quantify and measure against the intensity of staining expression within the tumour.

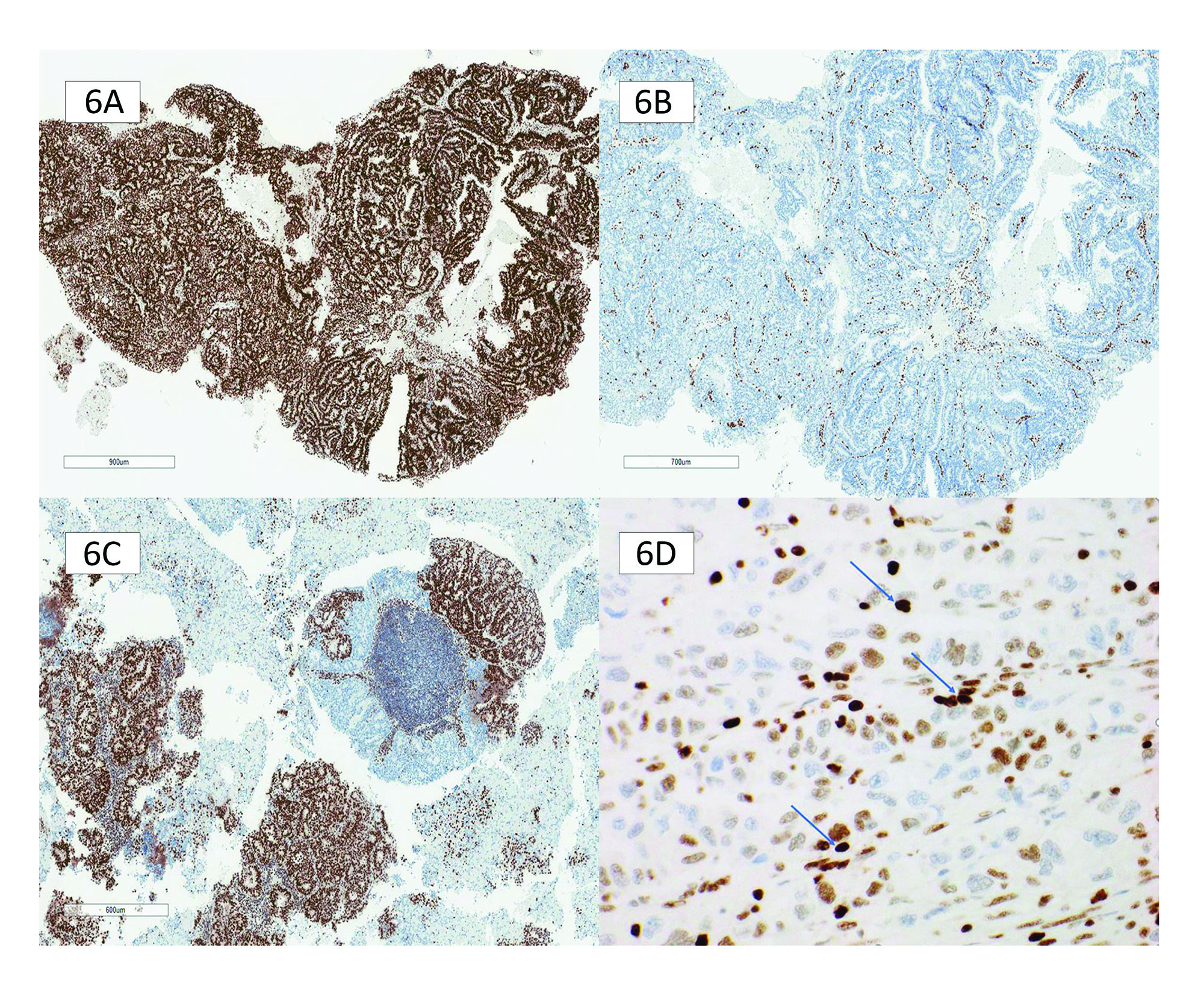

Defining intact and complete loss

Intact nuclear staining requires unequivocal nuclear staining with the same intensity as the internal control. The quality of the nuclear staining should be homogeneous and not punctate or membranous (Figure 6A).

Complete loss of staining should show an absence of nuclear staining within the tumour nuclei that cannot be explained by fixation artifact, with a retained internal nuclear control showing unequivocal nuclear staining (Figure 6B).

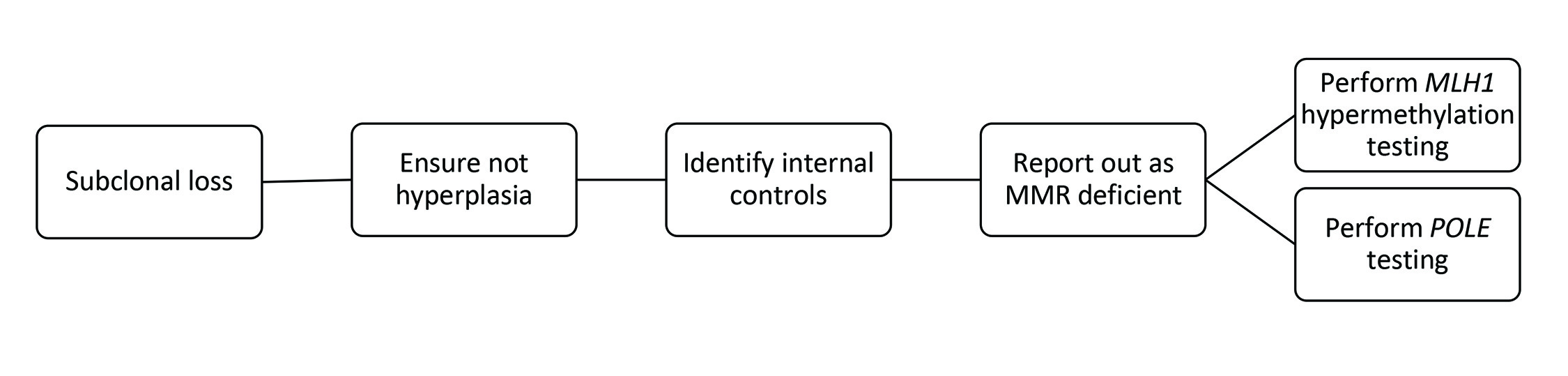

Subclonal loss

In both gynecological and gastrointestinal tumours, MMR protein loss in only a subset of tumour cells is called subclonal loss (Figure 6C). MMR protein loss can occur in only a subset of tumour cells, called "subclonal’ loss. Importantly, subclonal loss is defined as different areas with retained and lost nuclear staining, with intervening stromal cell positivity. Lynch syndrome germline mutations can be detected in endometrial and CRC patients whose tumours display solely subclonal loss of MMR staining. Reporting subclonal staining patterns is essential to ensure appropriate clinical follow-up. However, this is almost always attributable to an MLH1 subclonal loss due to MLH1 hypermethylation. Testing for MLH1 hypermethylation status will resolve this. Occasionally, a POLE mutation is identified. Figure 7 lists steps to perform when there is subclonal loss in EC.

Subclonal loss occurs when intact nuclear staining is present within the tumour sample, and an abrupt, complete loss of nuclear staining in an identifiable area with retained internal controls cannot be explained by fixation artefact or hyperplasia. This newer, well-recognized loss pattern warrants an initial MMR deficiency interpretation with further testing.

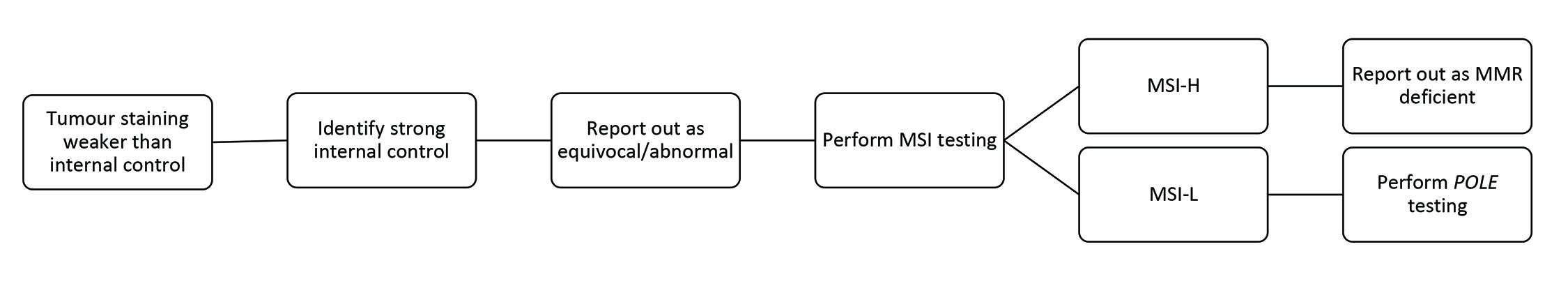

Weak staining compared to internal controls

Weaker than internal control staining is another recently recognized staining pattern. As the name suggests, this is identified as weaker MMR IHC tumour staining than the internal controls. The nuclei are not unequivocally homogenously stained and can have a variable appearance from nucleus to nucleus, which is not accounted for by fixation artefact (Figure 6D). Adjacent internal controls are key to identifying this pattern, as they will show unequivocal intact staining. Pathologists should recognize this pattern as it is often a cause for an overcall of MMR intact/proficient or MMR loss/deficient. An outright call is incorrect because neither accounts for a pathophysiologic explanation. Any MMR protein staining weaker than its internal control requires further interrogation.

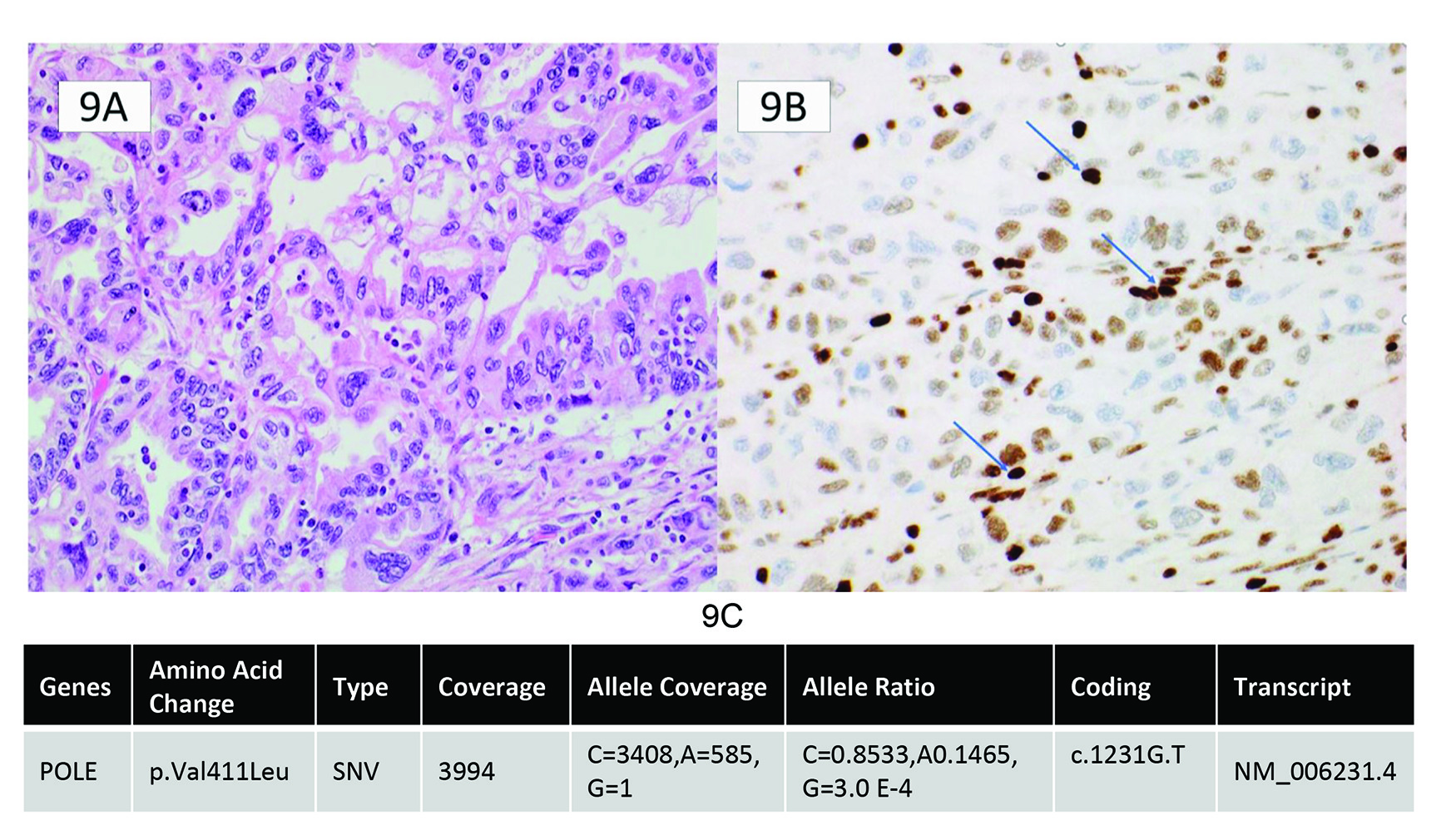

Two main explanations can account for weak nuclear staining of MMR proteins: true germline deficiency leading to misfolded protein and a weak protein expression, or a secondary passenger mutation causing weak staining compared to internal control. This type of staining is seen in both EC and CRC and highlights the importance of comparing the intensity of the internal controls to the tumoural nuclear expression. The MMR IHC interpretation should be reported as abnormal or uninterpretable if the tumour exhibits weak nuclear expression compared to internal controls. Repeating the IHC staining on another block is rarely helpful if there has been reasonable specimen fixation and there is robust nuclear staining in the internal control cells. An MSI PCR test can be used to determine the activity of the MMR complex, which, if MSI-high, identifies the tumour as having a germline or somatic MMR mutation leading to misfolded protein and weak expression. However, in cases of weaker staining compared to internal controls and a MSI-low (MSS) result on MSI testing, one must consider driver mutations in other genes, such as POLE, that can cause weak protein expression. POLE mutations, in particular, confer an ultra-mutated state caused by massive mutations in the genome. It is postulated that these mutations can also occur in MMR genes but are merely collateral damage, not the driver mutations for the tumour. This can result in only weak protein expression, not complete loss. POLE-mutated tumours also have ambiguous morphology which can overlap with MMR-deficient tumours, further highlighting the need for vigilance for this type of staining pattern. Figure 8 lists the steps to perform when tumour staining is weaker than internal control. An example of a tumour with ambiguous morphology and weaker than internal control staining and a pathogenic POLE mutation is seen in Figure 9.

Ultimately, MMR IHC is a triage test. If any non-normal result arises, reporting the finding as equivocal or abnormal and initiating further workup is recommended rather than reporting it as usual. Weak nuclear staining in MMR IHC compared to the internal controls should redirect the pathologist to pursue further testing to elucidate whether a true mutation exists.

INTERPRETIVE PITFALLS

The following sections discuss common interpretative pitfalls associated with different IHC staining patterns and their clinical significance.

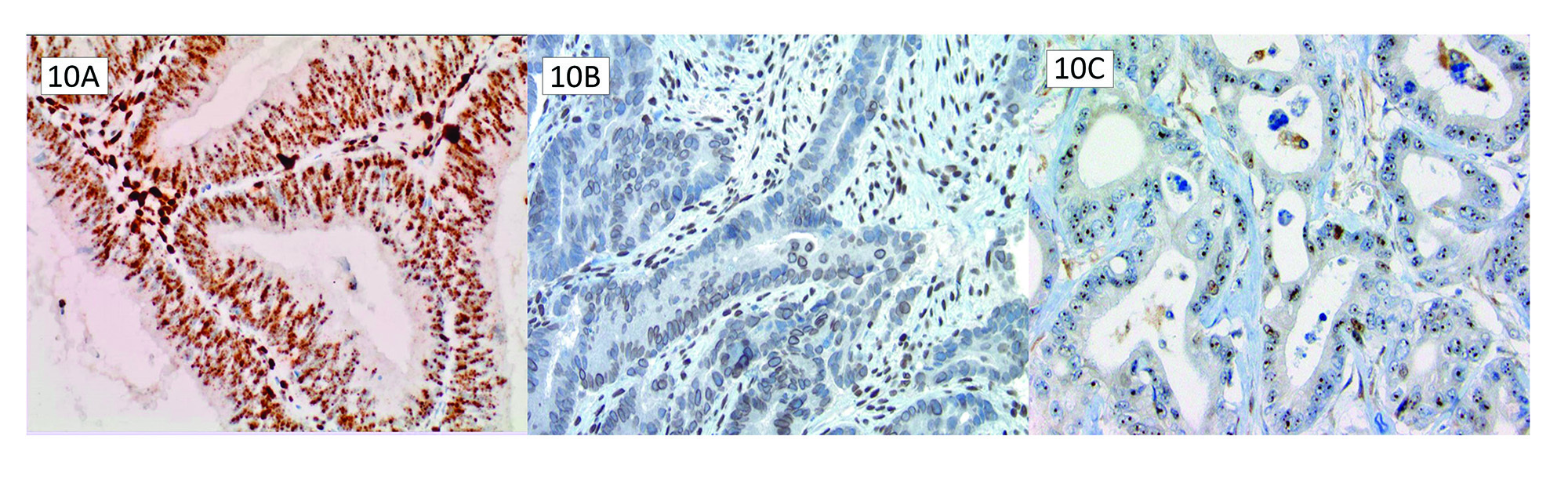

MLH1 punctate staining

Punctate speckled/nuclear MLH1 staining is a pattern confused with preserved MLH1 staining (Figure 10A). This pattern typically occurs concurrently with PMS2 loss and BRAF V600E mutation/MLH1 promoter hypermethylation. This punctate staining pattern can lead to erroneous isolated PMS2 loss reporting.21 It is likely an artefactual preserved staining due to technical issues with the staining protocol. Erroneously interpreting punctate nuclear staining as intact is unlikely to detrimentally affect patients as the germline panels in medical genetics will ultimately show this is not a germline PMS2 mutation; however, it can require additional resources and resolution required down the line when there is a discrepancy between MMR IHC results and germline testing as discussed below.

Nucleolar MSH6 and membranous MLH1 staining

True MMR immunoreactivity is solid nuclear staining. One must evaluate these patterns from at least 10X magnification to ensure there is no erroneous membranous MLH1 staining (Figure 10B) or nucleolar MSH6 staining (Figure 10C). These patterns are not evidence of preserved protein expression. There have been suggestions that prior chemoradiation can lead to nucleolar staining patterns of MSH6, but these patterns likely result from technical issues with the staining protocol.22 Undercalling MLH1 or MSH6 intact expression on IHC can potentially miss patients with Lynch Syndrome or an opportunity for therapeutic intervention. When these patterns appear under a microscope, they should be a reminder to investigate MMR status further with MSI PCR testing to clarify MMR protein function.

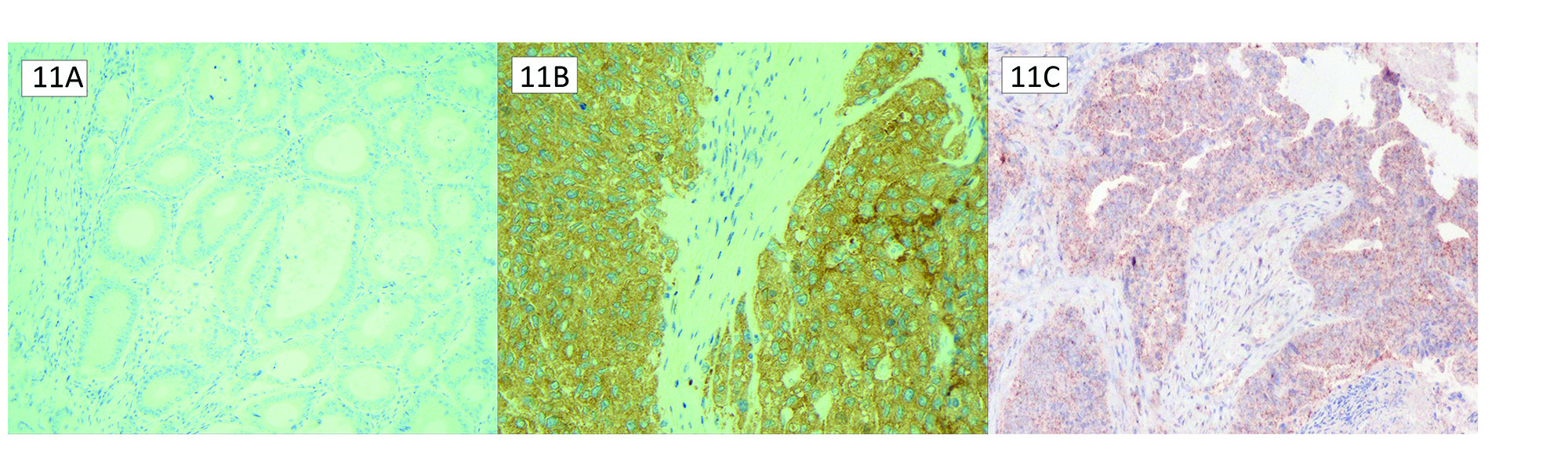

BRAF punctate staining

The most common BRAF mutation is the missense mutation from Valine 600 to Glutamic acid (V600E). Negative BRAF staining is easily identified as no cytoplasmic staining (Figure 11A). Positive cytoplasmic staining with BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry is highly concordant with its molecular testing counterpart (Figure 11B).23 However, like MLH1, BRAF can exhibit a discrete punctate nuclear staining pattern distinct from positive staining for the V600E mutation (Figure 11C). Nonspecific nuclear positivity is a known intrinsic property of the VE1 antibody. It is essential to be aware of this punctate pattern and not report it as mutational staining, as this can falsely attribute the MLH1/PMS2 loss to a sporadic pattern.

CLINICAL SCENARIOS

Questions about when to test in specific clinical scenarios arise with MMR testing in CRC and EC. Not all of these are guideline-specific, but they can be institutional-specific. The following section reviews common clinical scenarios pathologists face when working up MMR status in tumours.

Synchronous tumours

While the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the 2004 revised Bethesda guidelines recommend testing “all tumours” for microsatellite instability, implying that both synchronous tumours should be tested,24 the practice varies between institutions and pathologists. Two factors to consider are whether synchronous tumours increase the risk of Lynch syndrome and the clinical implications for when the MMR results are discordant between two synchronous tumours.

In CRC, multiple synchronous tumours are attributed to separate sporadic somatic genetic events and are not associated with unsuspected Lynch syndrome.25 Sporadic genesis is further supported over hereditary with over a 50% discordance rate between MMR status in synchronous CRC tumours.26 MMR analysis of CRC patients with multiple primaries may only find a small number of unsuspected Lynch syndrome cases.

In EC and ovarian carcinomas, synchronous tumours are most commonly metastases of one tumour to another location, rather than true synchronous primary tumours.26 As such, these do not increase the risk of Lynch syndrome more than a single primary.

If MMR testing is performed on both synchronous tumours, an issue arises when results are discordant. If the goal of testing is determining presence of germline Lynch syndrome, both synchronous primaries would be expected to show a loss of MMR status. A discordance in MMR results (intact versus deficient) suggests sporadic tumourigenesis. However, the prognostic and therapeutic implications could be more nuanced. Is the prognosis of the patient based on the worse tumour? Will oncologists treat the two tumours differently? No data supports any specific practice pattern, and clinical practice will vary depending on the oncologist and individual patient factors. Because practice is varied, it is crucial to consider the goals of MMR testing and how the results impact clinical decision-making when determining if MMR status is necessary for both synchronous tumours.

Recurrent tumours

Like synchronous tumours, the question of whether to re-test MMR status also arises with recurrent tumours. The rationale for repeat testing is less to identify a previously missed Lynch syndrome and more to uncover if new mutations have occurred in the recurrent tumour that changes the patient’s access to treatment. With MMR specifically, a new deficiency that previously did not exist would qualify the patient for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy.27

A study by Aird et al. of 150 patients with gastrointestinal or gynecological origin tumours showed a high concordance between initial primary and recurrent tumours.28 Of patients with MMR-deficient primary tumours, all recurrent tumours remained MMR-deficient. Of the patients with MMR-intact tumours, three cases (2%) were discordant with MMR-deficient recurrences. Further analysis of the discordant results showed that two of the three discordant cases were due to an incorrect interpretation of subclonal loss of MLH1. The third discordant case was a loss of MSH6 loss following radiotherapy.

In summary, MMR deficiency as a driving mutation is an early event in tumourigenesis. Recurrent tumours have high MMR status concordance with the initial tumour, with the leading causes for discordances attributable to initial interpretation errors and post-treatment changes. As such, repeat MMR testing in recurrence is of low yield for most patients. As first steps, we recommend ensuring a pre-treatment sample was tested and evaluated for MMR status and reviewing the initial MMR IHC sample for any subclonal loss or weaker staining compared to internal control that may have been missed. This practice can be used with a pathologist’s assessment of representative tumour tested (scant biopsy versus excisional specimen) to determine if repeat MMR testing is required.

Biopsy vs. resection for MMR testing

Biopsies have the distinct advantage of shorter ischemic time when evaluating biomarkers, one of the most critical pre-analytic considerations. Since MMR IHCs have considerable lability with poor fixation, biopsies are much preferred when evaluating MMR IHC. It also negates the pitfall of isolated MSH6 loss after chemotherapy in CRC specimens. An essential pitfall in biopsy MMR readout is the challenging differential between adenocarcinoma and hyperplasia in endometrial biopsies. The molecular characterization of EC on diagnostic biopsy samples is concordant with the subsequent hysterectomy sample. For MMR deficiency, biopsies had a PPV of 0.83 and an NPV of 0.97 relative to the final resection.29 However, two main challenges exist. Tissue availability presents an obstacle to complete characterization and may necessitate awaiting the resection sample.

MMR testing in tubular adenomas and atypical endometrial hyperplasia

In patients with a strong family history of Lynch syndrome who present with only colorectal adenoma(s), clinicians may sometimes request MMR testing; should pathologists test adenomas, and how should the results be interpreted and reported? Although MMR deficiency commonly precedes adenoma formation in Lynch syndrome patients,30 studies regarding Lynch syndrome screening in young patients (less than 50 years old) with adenomas have shown a low yield of positive results with a prevalence of 0.4%.31,32 However, older age and high-grade dysplasia in adenomas increase the likelihood of MMR deficiency.33

Based on these factors, we do not recommend routine MMR testing in young patients with adenomas. If tested, we recommend interpretation in this subset of patients as follows: if testing identifies MMR deficiency, this is likely an accurate result considering the pathogenesis of Lynch syndrome, and should be reported as true MMR deficiency. In cases of high clinical suspicion of Lynch Syndrome and MMR preservation, consider a report comment that IHC sensitivity in patients with Lynch syndrome is 50-70%, and these patients may warrant a referral for germline testing regardless of their intact IHC results.

MMR IHC evaluation is being for more commonly in oncofertility clinics for young patients with atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Small studies have shown that atypical endometrial hyperplasia, which is a driver of MMR deficiency, can result in a lower response rate to progestin and an increased recurrence rate.34,35 A meta-analysis has recently been completed that shows similar findings.36 There is not enough evidence to recommend in this situation, except to complement the adenoma section that there is a low yield in screening every patient with atypical endometrial hyperplasia for MMR deficiency. If there is a clinician request, an MMR deficient result in a specific clinical context is likely accurate and should be reported as a true MMR deficiency. However, an MMR intact result in atypical endometrial hyperplasia does not preclude a possible deficiency should the patient progress to adenocarcinoma, and should be retested for MMR deficiency at that time.

DISCORDANT RESULTS

Depending on the staining pattern, loss of MMR proteins on IHC will prompt germline testing, and occasionally, MMR status as determined by IHC results will not match the results of germline testing. It is essential to consider the variety of potential causes for this discrepancy in these situations when attempting to reconcile the discordant result. The following section will review the causes of a discordant MMR IHC and the germline testing result.

Neoadjuvant therapy

Isolated MSH6 loss on IHC reflects a high risk of Lynch syndrome and typically directs patients to Medical Genetics. Of note, neoadjuvant chemo- and radiation therapy can cause an extensive loss of MSH6 on IHC in CRC.37 The chemotherapy regime for CRC uses antimetabolites, which incorporate during cell division, and alkylating agents, which affect the cell during rest and affect not just protein expression of MSH6 but have also been shown to express other IHC markers, such as Ki-67.37 The use of radiotherapy then potentiates this loss. The isolated loss of MSH6 following neoadjuvant treatment does not predict an underlying MSI phenotype, and when examined, these patients’ tumours usually show microsatellite stability. Despite the MMR loss on protein expression, the pathophysiology of how the MSH6 expression was lost is incompatible with a microsatellite instability phenotype, and, therefore, the patient is expected to have the same response to immunotherapy, nor need a referral for medical genetics. The identification of isolated MSH6 loss in treated tumours should prompt the pathologist to evaluate the pre-treatment biopsy results first.

EPCAM mutation associated MSH2 loss

Upstream EPCAM mutations to the MSH2 locus can include deletions identified on the terminal exons of EPCAM, leading to the transcriptional elongation from EPCAM directly into MSH2. This results in an abnormal non-functioning fusion.38 In clinical practice, this mutation manifests as a patient with a strong Lynch syndrome phenotype or a family history of MSH2 loss on IHC but no MSH2 mutation on sequencing. This combination of IHC and germline results with the patient history should prompt consideration for EPCAM sequencing; indeed, current large germline panels typically include EPCAM. A final caveat with EPCAM mutation-associated MSH2 loss is that EPCAM expression is tissue-dependent, and tumourigenesis is more likely to arise in high EPCAM expression in epithelial tissues.39

Loss of multiple MMR IHC

Loss of multiple MMR proteins on IHC can typically be attributable to MLH1 hypermethylation or occasionally POLE mutation-related ultra-mutated phenotype instead of numerous independent germline mutations in MMR or a technical issue with the platform testing.40,41

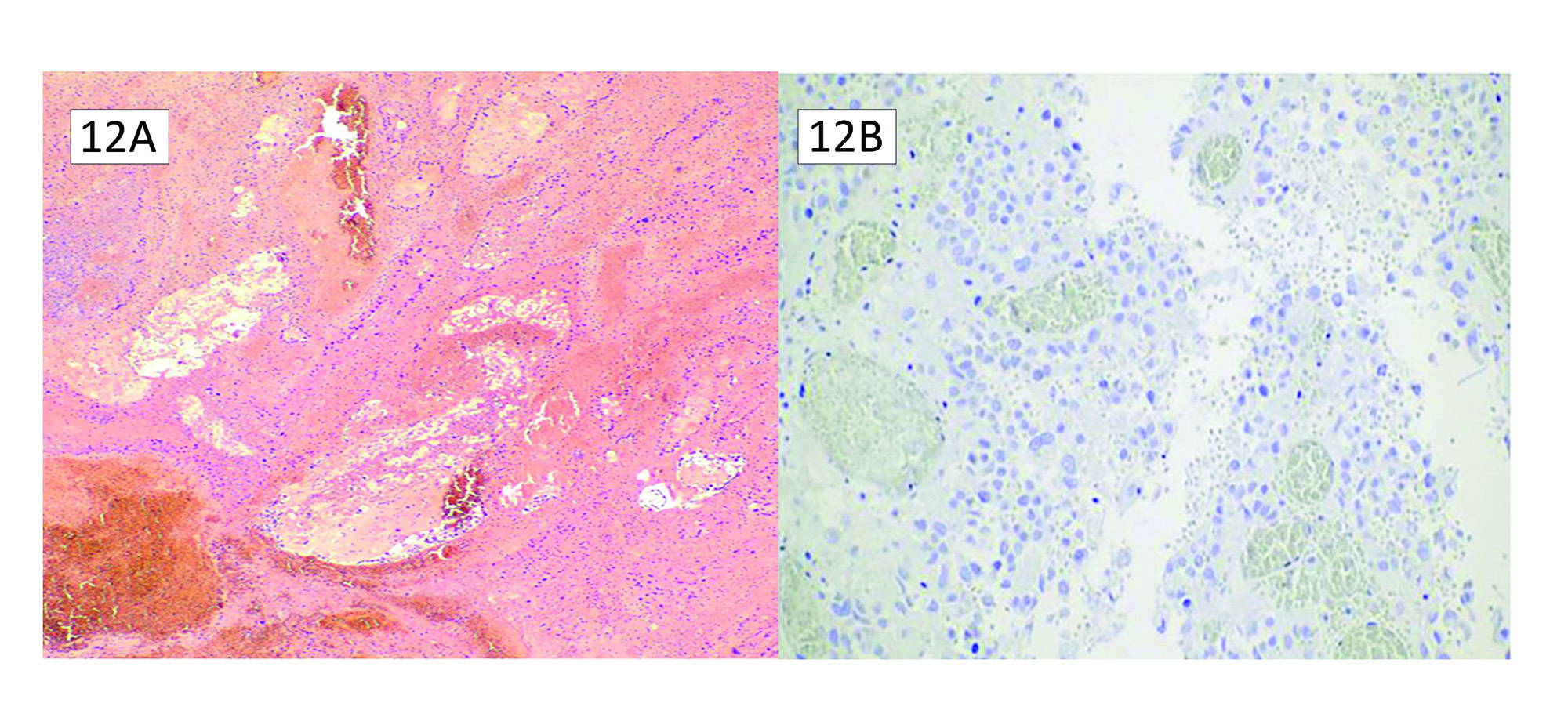

“Lynch-like” Syndrome

“Lynch-like” syndrome is described as deficient MMR protein analysis on IHC without MMR germline mutations, no EPCAM mutations, and no evidence of BRAF mutation or MLH1 hypermethylation. These situations account for approximately 30% of patients with abnormal MMR protein expression.42 Table 3 summarizes the possible causes of Lynch-like syndrome. First, and probably easiest to evaluate, are false-positive MMR IHC results. When faced with a discrepancy between the IHC results and germline testing, it is prudent to re-evaluate the MMR stains and consider any equivocal stains to confirm the presence of abnormal MMR protein expression. Figure 12 shows an ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma that was called MSH6 deficient and went on to show no germline mutations. A review of the H&E shows extensive necrosis and ischemic change caused by torsion, leading to likely poor antigen retrieval. It is observed in Figure 10 that there is no internal control present, either. Secondly, some patients may have a germline mutation that current testing methods have failed to detect.

An example is the inversion of MSH2 exons 1-7, which many commercial genetic laboratories do not detect. There have been reports of somatic mosaicism that may explain Lynch-like syndrome in rare cases.43 Other germline genetic defects may explain Lynch-like syndrome. In one recent study, 21% of patients with Lynch-like syndrome had biallelic MUTYH mutations.44 Lastly, and commonly, recent literature reports have identified biallelic somatic mutations in MMR genes in many tumours in patients with Lynch-like syndrome.45 Biallelic somatic mutations of MMR genes are likely sporadic events, suggesting that such tumours are most likely cancers with sporadic MMR deficiency instead of hereditary mutations.

Constitutional MMR deficiency

Lynch syndrome results from a heterozygous germline mutation of MMR proteins, leading to an elevated risk of CRC, EC, and other malignancies, typically manifesting from the fifth decade of life. In contrast, constitutional MMR deficiency syndrome (CMMRD) results from inherited biallelic mutations in MMR proteins, leading to early and significant manifestations of malignancy in these patients. Detection of pathogenic variants in both alleles of an MMR gene is required to confirm the diagnosis of CMMRD. Still, molecular genetic testing confounds MMR variants of unknown significance and pseudogenes of PMS2. The hallmark of CMMRD is the detection of low-frequency microsatellite length variants in nonneoplastic tissue,46 and immunohistochemical screening with MMR proteins can be arduous due to the loss of staining in both neoplastic and nonneoplastic cells, rendering an inadequate internal positive control. It is important to be conscientious of CMMRD, particularly in the cases of young patients with MMR deficient cancer history with dual MMR deficiency IHC staining pattern loss in both neoplastic and nonneoplastic tissue.

Constitutional MLH1 hypermethylation

In constitutional MLH1 hypermethylation, a hypermethylated allele can be inherited from a parent or arise early in embryogenesis to result in a hemi-allelic genotype. Subsequent inactivation of the unmethylated allele provides the second hit in tumourigenesis.47 Patients with this genotype present with a Lynch syndrome phenotype, and it has been estimated that constitutional hypermethylation accounts for 1-10% of all Lynch syndrome.47 A significant caveat when considering constitutional MLH1 hypermethylation is the epigenetic reversibility of DNA methylation. Epigenetics describes genetic modifications that affect gene function and expression but do not involve changing the identity of the nucleotides. These include various methylation patterns, acetylation, phosphorylation, and other modifications to either DNA or histones. During DNA replication, DNA methylation does not replicate faithfully and can result in some cell populations with high methylation density and others with low methylation density, resulting in methylation mosaicism.47 The inheritability and penetrance of this epimutation are varied and unpredictable—close surveillance for patients and their families with this epimutation.

POST-TEST CONSIDERATIONS

The pathologist improves lab quality and provides diagnostic and prognostic information. The following sections describe post-test considerations for MMR to ensure an accurate and understandable readout.

Standardized language and reporting

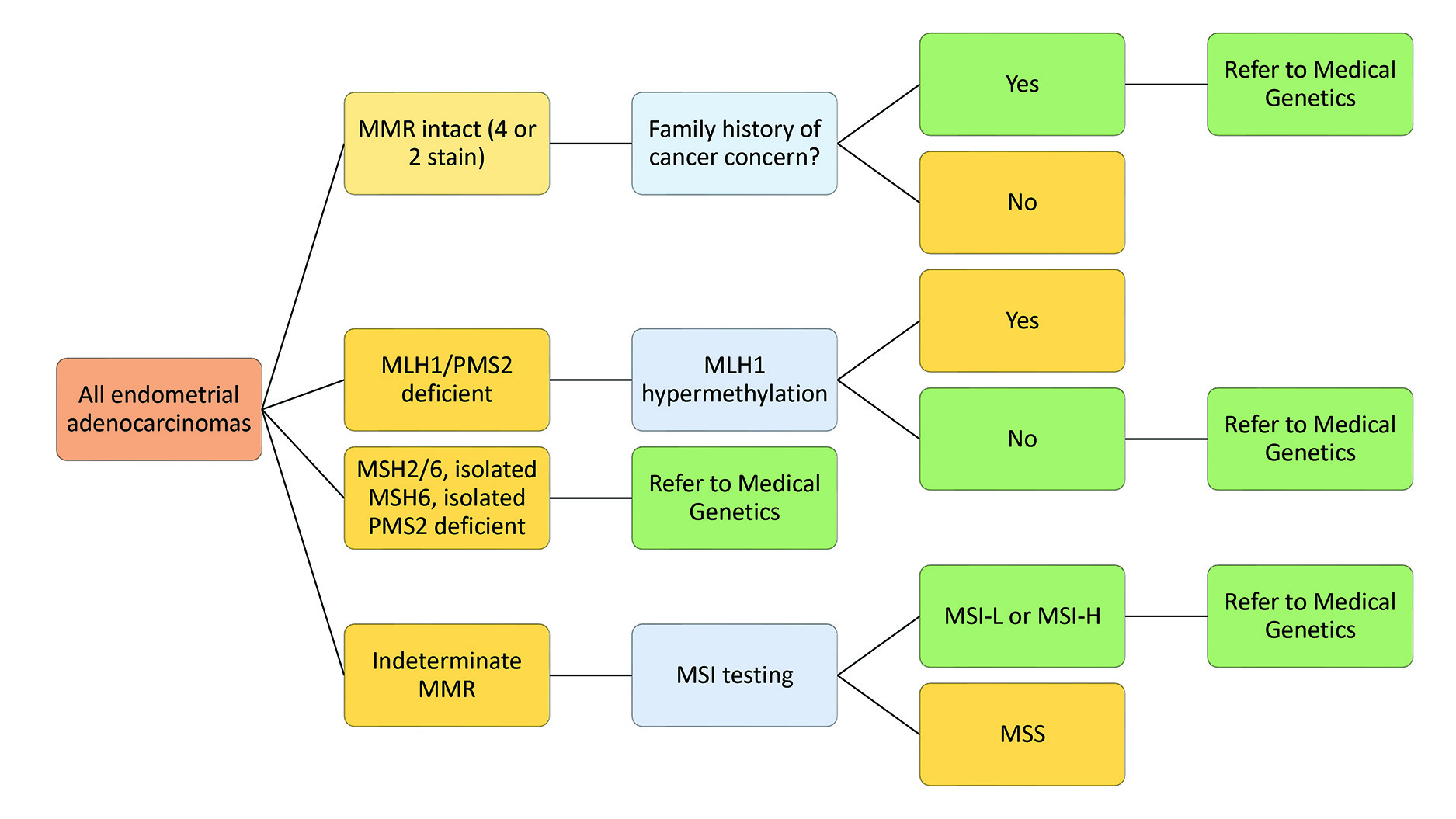

The College of American Pathologists (CAP) provides a guideline and template for reporting MMR results.48 Templates like CAP streamline the reporting process for pathologists, prevent accidental omission of information in reports, and make reports easier to read for clinicians. It is also essential to consider the clinician’s needs and include specific guiding statements to communicate effectively. This includes guiding statements about which patients should be referred to medical genetics. Figure 13 shows the algorithm for referral for both gynecologic and colorectal patients.

Technical proficiency

Controls for type II biomarkers can be external on-slide positive controls or internal controls such as stromal cells or tumour infiltrating lymphocytes. The current consensus amongst experts is that internal controls are ideal for class II testing when appropriate readout proficiency.49 While not mandated, pathologists can assess the accuracy of readout among other biomarkers via the Canadian Biomarker Quality Assurance readout external proficiency testing tool to ensure competency and confidence when signing out these cases.

Quality audits

Comparing individual and institutional test results and overall population statistics for MMR allows for identification of discrepancies and potential concerns, such as overcalling MMR deficiency, technical issues with sample antigen preservation and antigen retrieval, and poor tissue fixation. Two extensive population studies for colorectal and gynecologic cancers can be used for matched control population quality metric development.50,51

CONCLUSION

MMR testing contributes immensely toward the clinical decision-making process for CRC and EC, carrying important therapeutic, diagnostic, and prognostic implications for the patient and their oncologists. MMR IHC is a deceptively simple test. However, it contains pitfalls that can be challenging and lead to over- and underreporting for those unaware of its nuances. It is also the gateway to further genetic and molecular workup. This critical position in both CRC and EC underlies the need for pathologists to have an intimate understanding of the biology and clinical implications of MMR deficiency, ensuring that the information the pathologist provides to the clinician is relevant and accurate.

This manuscript was peer-reviewed.

Disclosures

Dr. Kinloch and Dr. Schaeffer have received travel bursaries from CAP-ACP to visit Canadian Laboratories to provide MMR educational read out seminars.

The authors declare that there are no undisclosed conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper. All authors have provided Clockwork Communications Inc. with non-exclusive rights to publish and otherwise deal with or make use of this article, and any photographs/images contained in it, in Canada and all other countries of the world.

ISSN 2819-2842